Micromobility in Smart Cities

Over the past two years, first in the US and then in Europe, two-wheel micromobility in the form of shared electric bikes, scooters, and motorbikes has become ubiquitous. What has made this a success with consumers is the highly convenient combination of electric traction and dockless operation, in stark contrast with non-electric, docked shared bike schemes launched in many cities across the globe, but never reaching high usage rates.

Finding a nearby two-wheel vehicle on the fly via a smartphone app and seamlessly unlocking, using, and paying for it echoes the ease of the car sharing experience commercialised by Uber. Additionally, micromobility benefits from the fashion trend of new last-mile mobility, bridging the gap with public transport, avoiding congestion experienced by four-wheel vehicles, and, most importantly, doing away with the thorny issue of parking in cities worldwide.

However, the advantages of micromobility go beyond people mobility. Two-wheel vehicles have also been massively adopted for transporting food ordered online, with pizza delivery bikes already having become iconic.

The benefits of micromobility are obvious, both in terms of the positive impact on congestion levels and air pollution, challenges with which many cities worldwide have been struggling. Even with a modal share of between 10% and 20%, electric micromobility removes or replaces enough four-wheel vehicles on the road to materially impact traffic flow and air quality.

Walking, scooting and cycling are now more viable alternatives for short journeys. As more citizens begin working from home or cycling to work, public transport becomes a more attractive option for those looking to take longer trips. By focusing on mobility, and developing more sustainable and accessible ways to navigate the city, city developers can turn the Coronavirus crisis into a real opportunity for change.

Smart cities can only be built on smart streets, and when you build to improve the lives of citizens, then everybody wins.

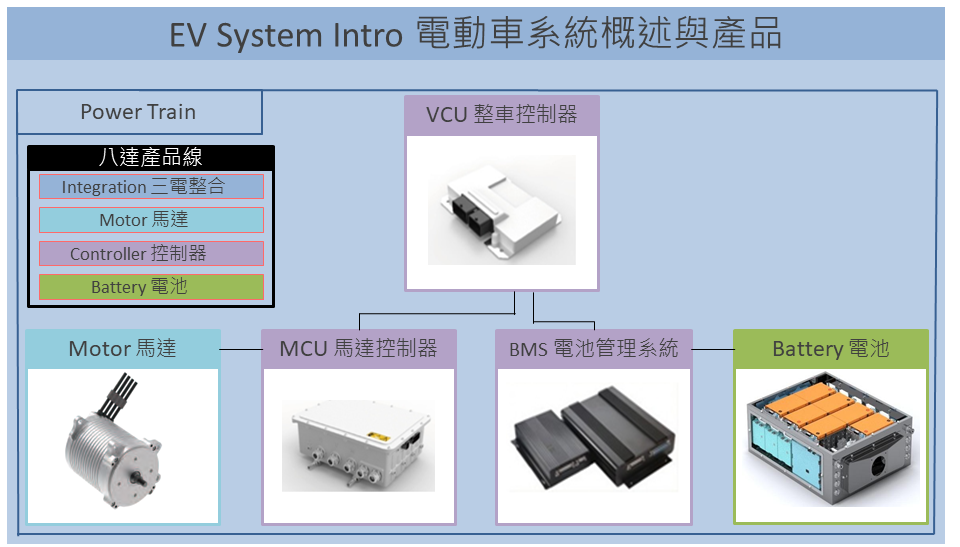

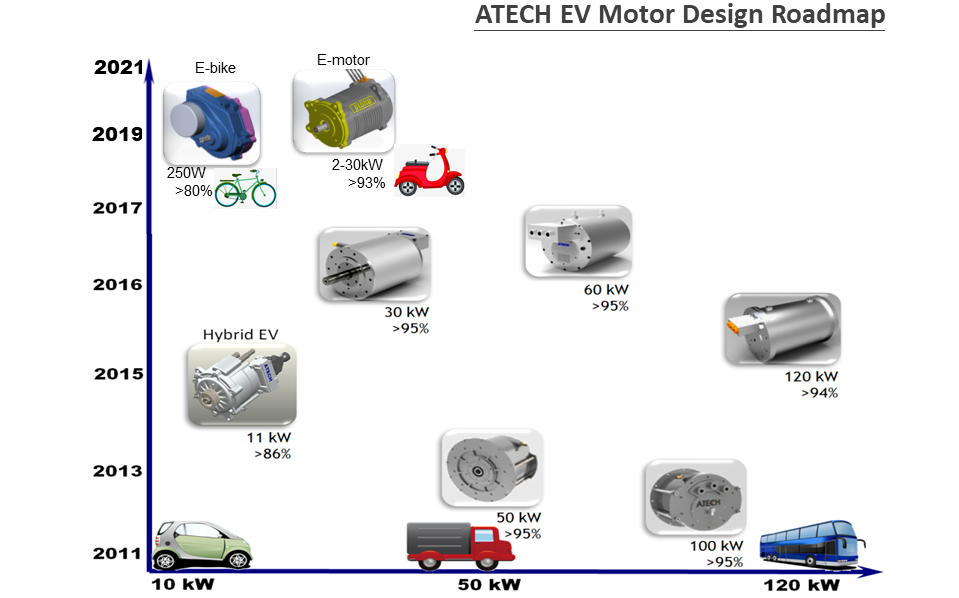

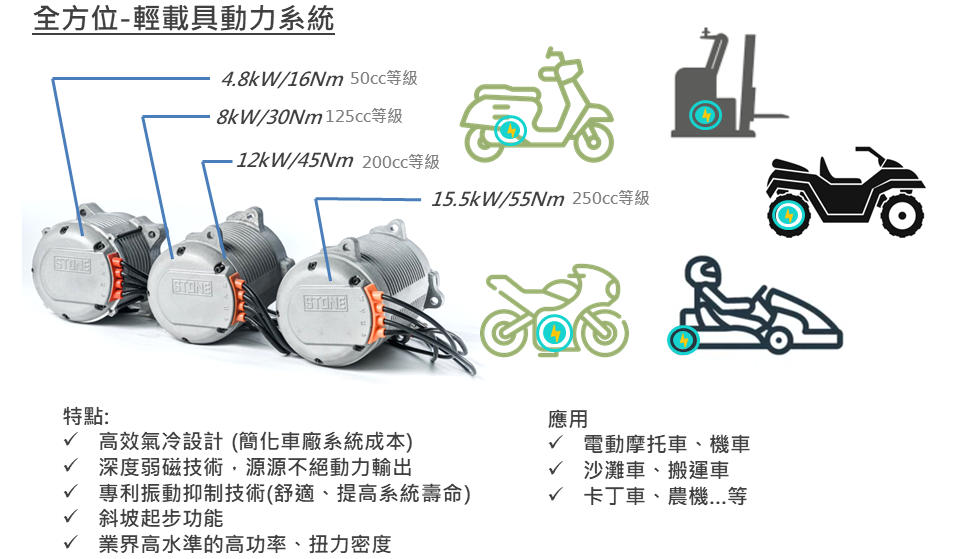

緣於其相關企業磐石電池與八達創新科技公司,開發電動車動力電池以及電控系統有成,並鑑於台灣數十年來相關産業盡從事工業用交流感應馬達,而陌生於電動車需要高效率節能的永磁同步馬達,於西元2000年召集工研院以及產業界菁英創立永固開發工業股份有限公司,專注電動車馬達開發

緣於其相關企業磐石電池與八達創新科技公司,開發電動車動力電池以及電控系統有成,並鑑於台灣數十年來相關産業盡從事工業用交流感應馬達,而陌生於電動車需要高效率節能的永磁同步馬達,於西元2000年召集工研院以及產業界菁英創立永固開發工業股份有限公司,專注電動車馬達開發